Expressionism is a mode of representation whereby internal feelings and abstract concepts are displayed externally, often at the expense of realism and artistic convention.

Expressionist art usually has a surreal or fantastic quality to it, presenting distorted aesthetics through which the true nature of a thing is belied in its external countenance. It is an artistic movement that evolved from European Romanticism and continues to influence a variety of artistic mediums, including literature, music, architecture, theatre and cinema.

In filmic terms, expressionism manifested itself visually in the distinctive mise-en-scène and cinematography of 1920s German cinema. The look of these films was often characterised by the use of chiaroscuro lighting, Dutch camera angles, two-dimensional sets and over the top performances. In narrative terms, expressionist films were often preoccupied with dark subject matter such as evil, madness and the occult.

Director Tim Burton has on several occasions expressed an affinity for the works of expressionist artists: "It was the strength and simplicity that I really loved about the expressionists' work. That and the fairy-tale element." Their influence is clearly visible in many of Burton's films, including his two comic book ventures, Batman (1989) and Batman Returns (1992).

Perhaps the most obvious example of this would be the depiction of Gotham City itself. Prior to shooting Batman, Burton met with acclaimed comic book writer Alan Moore, who told him to "get Gotham City right". In his original script for The Killing Joke (1988), Moore directly likens the look of Gotham City to Robert Wiene's expressionist classic The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920). Burton evidently took this description to heart, and the architecture of Gotham is merely one of many aspects of the Batman films to be inflected by his expressionist sensibilities.

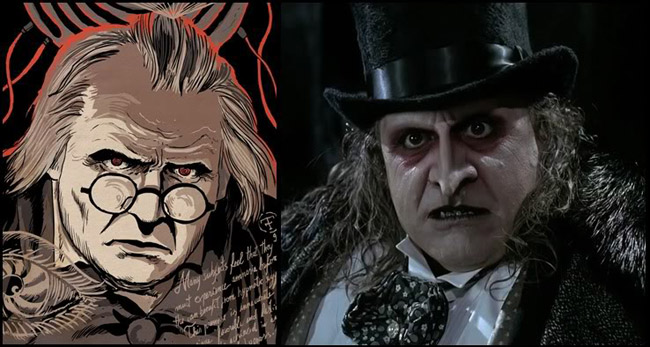

Oswald Cobblepot - A Postmodern Caligari

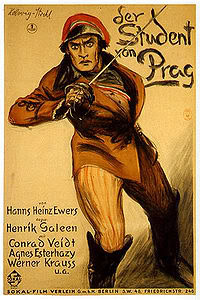

Expressionist cinema, like expressionist theatre, would often use exaggerated character types to populate its equally exaggerated vistas. Once such character type was the short, fat, sinister professor/magician; perhaps the most famous example of which would be the eponymous character from Robert Wiene's The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. Caligari was one of several such characters portrayed by veteran actor Werner Krauss. Others included the characters of Scapinelli in The Student of Prague (1926) and Spring-Heeled Jack in Paul Leni's Waxworks (1924).

Visually, these characters shared a lumbering gait, rotund physique and leering grin. They were usually depicted wearing a top hat, long coat and carrying a walking cane. It was a character type partially informed by the anti-Semitic sentiments of the age, as well as the traditions of early 20th century German theatre. The depiction of Oswald Cobblepot/The Penguin in Batman Returns is a clear descendant of this model, sharing more than a passing similarity with Krauss' portrayal of Caligari.

Interestingly, when Batman Returns was first released in 1992, The New York Times published an article titled "Batman and the Jewish Question" in which journalists Rebecca Roiphe and Daniel Cooper accused the film of having an anti-Semitic subtext. Roiphe and Cooper picked up on the film's Wagnerian overtones and Biblical allegory (the murdering of the first born sons) and concluded that the filmmakers had consciously imbued the film with an anti-Jewish subtext. This in turn prompted Batman Returns' screenwriter Wesley Strick to respond in a written letter, refuting the accusations and stating "It's your article, not our film, that is divisive."

Such an interpretation, though clearly unintended by the filmmakers, can nevertheless be seen as an inherited by-product from the Weimar era.

"Not a lot of reflective surfaces in the sewer, huh?"

Mirrors are a recurring visual motif in Burton's Batman films. The villain's aversion their own reflection emphasises their inability to confront the disparate nature of their fractured psyches. Rather than face their problems head-on, they turn their backs on them and allow their darker sides to reign supreme. This visual device for representing internal duality was a common one in expressionist cinema. It was used in F. W. Murnau's Nosferatu (1921) to suggest the two-sided aspect of the protagonists' psyches, and served a similar function in a number of later expressionist works.

|

In Henrik Galeen's The Student of Prague, the character Balduin (Conrad Veidt) sells his reflection to magician Scapinelli (Werner Krauss), prompting the reflection to step out of the mirror and take on a life of its own. The doppelganger continues to haunt Balduin until the latter destroys the mirror whence it originated; freeing himself of his darker side but inadvertently destroying himself in process.

This act of destroying/liberating a secondary aspect of one's personality through a mirror is also seen in F. W. Murnau's Faust (1926), where Mephisto (Emil Jannings) bestows youth on Faust (Gösta Ekman) by capturing his aged countenance in a small mirror. At the end of the film, Mephisto smashes the mirror and Faust is once again deprived of his youth. In this context, the mirror becomes a transitional object connecting the old Faust with the young Faust. By destroying the mirror, the two identities are permanently separated.

The mirror motif in Burton's Batman films operates as a similar transitional image. Jack Napier's introductory scene shows him standing in front of a mirror admiring his own reflection. Later, upon seeing his mutilated face for the first time, he promptly destroys another mirror. It's interesting to note that, as in Alan Moore's The Killing Joke, the point where the Joker goes insane is not when he emerges from the chemicals, but when he sees his reflection for the first time.

Amongst the articles of furniture Selina Kyle destroys during her transformation into Catwoman is a mirror hanging on the wall. In doing this, she is rejecting her old self and asserting a new self-destructive personality to usurp its place. Later in the film, in a scene that pays homage to Roman Polanski's Rosemary's Baby (1968), Selina is out Christmas shopping and becomes transfixed by the sight of her own reflection in a shop window. She stares at the window and asks herself "Why are you doing this?" This visual representation of a dual personality is remarkably similar to that displayed 70 years earlier in the films of Galeen and Murnau.

From Metropolis to Gotham

One of the crowning achievements of expressionist cinema was Fritz Lang?s 1927 film Metropolis. This film's production design set a precedent that would continue to influence filmmakers right up to the present day. From Ridley Scott's Blade Runner (1982) to Luc Besson's The Fifth Element (1997), Metropolis' lineage has left a distinctive trail throughout modern cinema. It was the most expensive silent film ever made, costing around 5,000,000 Reichsmark and effectively bankrupting the studio that made it.

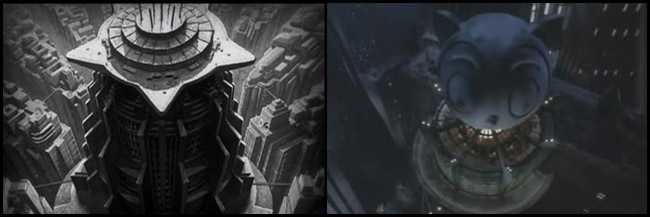

For Batman Returns, Burton's production team went for a neo-fascist aesthetic reminiscent of the iconic visuals displayed in Lang's picture. Characterised by harsh, angular skyscrapers and art deco interiors, Gotham took on more of a 1920s look that nicely complimented the film's dark, almost black & white cinematography.

Tom Duffield - who served as Art Director on several of Burton's films - has acknowledged the connection with Lang's work, confirming that "the interiors of the Shreck building did have a Metropolis influence". If we compare the overhead establishing shot of the "Tower of Babel" from Metropolis with the similarly framed/angled shot of the Shreck building in Batman Returns, we can see how the exterior design of the latter film is equally indebted to that of the former; the one major discrepancy in this example being the irreverent addition of a giant grinning cat's head in Burton's film.

But Metroplis' influence on the Batman films extends beyond the visual design. The showdown at the end of Batman is remarkably similar to the finale in Lang's film. Both take place in a derelict cathedral, anachronistically located amidst the spiralling skyscrapers of an otherwise futuristic setting. The villain ascends to the top of the cathedral with the central love interest in tow, compelling the hero to pursue them and do battle against the crumbling parapets. A crowd of spectators gather at the cathedral steps to watch the battle and witness the villain plummet to their death while the leading lady hangs on for dear life.

The American Legacy

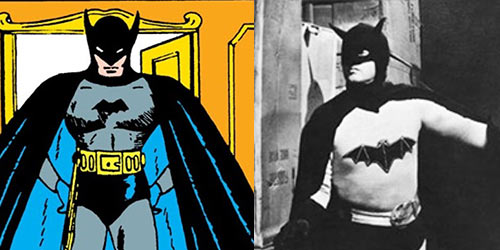

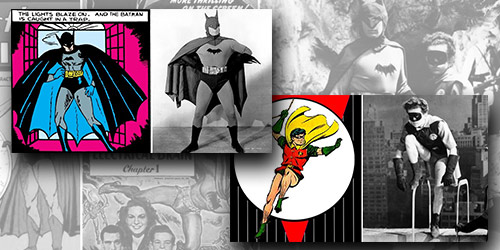

Any discussion of the expressionist influence on the Batman franchise would be remiss for not mentioning Paul Leni's 1928 film The Man Who Laughs. Produced by Universal Pictures, the film starred Conrad Veidt, who had previously collaborated with Leni on the classic German expressionist film Waxworks just four years earlier. Veidt's character, Gwynplaine, served as the visual inspiration for Bob Kane and Bill Finger's depiction of the Joker in the early comics. Gwynplaine's permanent grin also inspired the Joker's grotesque countenance as seen in Burton's Batman; with both characters' faces frozen in permanent rictus grins so that they are unable to stop smiling, even when they want to. The ambiguous effect of this image is just as haunting in Burton's film as it was in Leni's.

Leni himself was a German expatriate who emigrated to America at the behest of film producer Carl Laemmle (founder of Universal Studios). Interestingly, Producer Carl Laemmle was also a German expatriate and a prominent filmmaker in Weimar Germany. Amongst the American pictures he produced was the 1925 film The Phantom of the Opera, a movie Burton paid homage to in Batman Returns during the masquerade scene when a partygoer (allegedly played by Burton himself) appears on the stairway dressed as the Red Death; a homage to Lon Chaney's appearance at the ball in the 1925 film.

These are just a few of the connections between Burton's Batman films and the expressionist movement of the Weimar Republic. The distinctive style of 1920s German cinema went on to influence other film genres such as film noir and horror, which in turn have continued to inspire Batman comic writers and filmmakers right up to the present day.

Tim Burton, quoted "Tim Burton and Vincent Price" by Graham Fuller, Interview (December, 1990)

Alan Moore, quoted in "Moore's Murderer" by Steve Rose (February, 2002), Guardian.co.uk (accessed May 2010): http://www.guardian.co.uk

Wesley Strick, "Anti-Semitism in 'Batman Returns' Be Serious; Who's Really Divisive?" (July 20, 1992), The New York Times (accessed May 2010): http://www.nytimes.com

Clive J Matthews & Jim Smith, Virgin Film Guide: Tim Burton (London: Virgin Books Ltd, 2002), p. 114

by The Laughing Fish

by The Laughing Fish

by The Laughing Fish

by The Laughing Fish

by The Laughing Fish

by The Laughing Fish

by The Laughing Fish

by The Laughing Fish

by The Dark Knight

by The Joker