INTRODUCTION

The phrase ‘Red Batman’ is one I’ve seen crop up numerous times on the internet. It suggests a correlation of tone and character between DC’s Dark Knight and Marvel’s Man Without Fear; a correlation which is implicitly plagiaristic in nature. If Daredevil is Marvel’s Batman, then Marvel must have stolen elements from Detective Comics, right? It’s easy to see how the comparisons arose. Both comics star ostensibly ordinary heroes who rely on athleticism, martial arts skill and advanced intellect to keep the streets of their hometown clean from crime. And both comics are characterised by a dark and gritty tone that blends urban crime drama with elements of fantasy fiction. Of course there are plenty of other, more specific similarities between the two titles, some of which I’ll explore in this feature. But for every similarity I could note, there are an equal number of differences. So why do some people insist Daredevil is a rip-off of Batman?

The most likely answer is that these people have had limited exposure to the Daredevil comics. As far as there being a Marvel equivalent to Batman, there are several other characters who fit the bill better than Daredevil. Take Moon Knight, for instance. When Matt Murdock first appeared back in ‘The Origin of Daredevil’ (Daredevil Vol 1 #1, April 1964), the Batman comics were entering their ‘New Look’ era; a period where writers were consciously steering away from the extravagant science fiction and fantasy stories of the fifties in favour of detective narratives similar to those of the Golden Age. But Batman was still very much grounded in the Silver Age tone, as was Daredevil. Besides that, the two comics bore little resemblance to each other. If anything, the early Daredevil stories were much closer to the Spider-Man comics than Batman.

Mark Waid jokingly referenced the Batman comparisons in Daredevil Vol 3 #24 (March 2013).

As the Silver Age neared its conclusion and the Bronze Age loomed on the horizon, American comics in general began to abandon the levity of the sixties and adopt a darker, grittier tone; one that was reflective of the cynicism prevalent in the American cinema of that period. Batman and Daredevil both underwent drastic changes in accordance with this trend. But which character went dark first? Conventional views hold that Frank Miller returned Batman to his darker roots in the mid-eighties. More accurate perspectives cite the Denny O’Neil/Neal Adams run from 1970 onwards as the true rebirth of the Dark Knight. While the most well-informed Batman historians recognise the Frank Robbins/Irv Novick run as the one that really set the darker Batman back in motion from 1968 onwards.

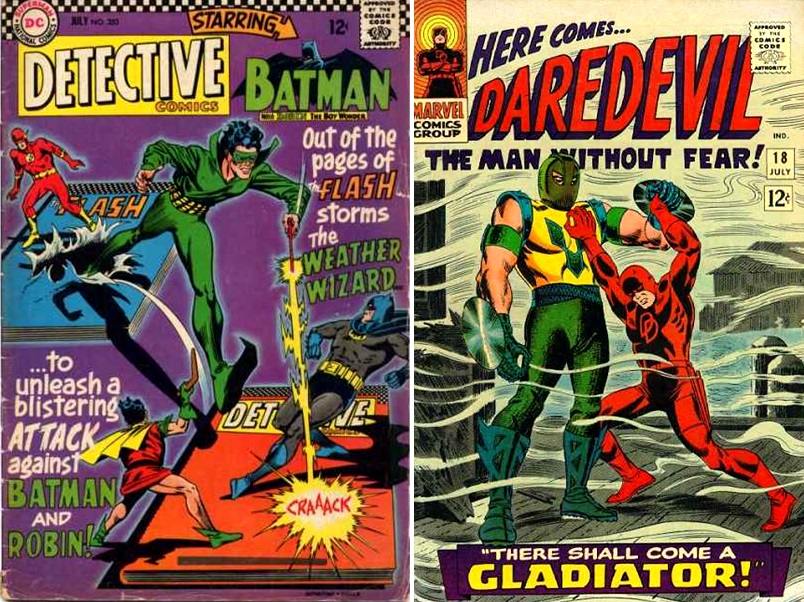

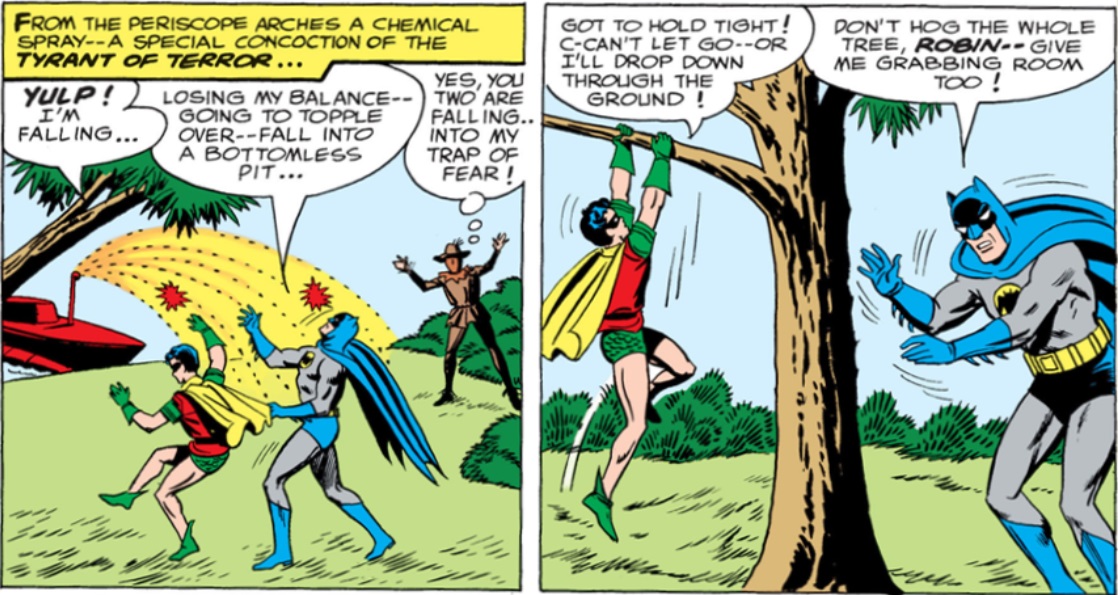

The thing is, even though there were grittier Batman comics as early as 1968, the majority of Batman titles back then were still fairly fantastical and light in tone. Compare the following comic covers, both dated from June 1966.

One shows Batman and Robin teaming up with the Flash to fight a costumed troublemaker (Weather Wizard) wielding a magic wand; the other shows a battle-wearied Daredevil grappling with a saw blade-wielding psychopath (Gladiator) on a fog-shrouded waterfront at night. My main reason for selecting these two covers for comparison, besides the fact they were both published in the same month, is that this particular issue of Daredevil was the first to be written by Dennis O’Neil – three and a half years before he ever put pen to a Batman script.

O’Neil would write numerous issues of Daredevil and even serve as editor during the early eighties. In fact it was O’Neil who fired Daredevil writer Roger McKenzie and appointed his replacement: an up-and-coming talent named Frank Miller, who by that point had already pencilled several issues based on McKenzie’s scripts. Miller was paired with artist Klaus Janson while O’Neil stayed on as editor. The comics they produced during this period are now widely regarded as the definitive Daredevil run; the one that established the tone which almost all subsequent creators would endeavour to follow.

O’Neil himself would later edit numerous Batman titles from 1986 onwards. His greatest editorial contribution that year was to reunite the creative team of Miller and Janson on another acclaimed run, this time for DC Comics. This four-issue miniseries would ultimately come to be known as Batman: The Dark Knight Returns. Meanwhile O’Neil and Miller would work together on yet another Batman story in 1987, this time bringing in David Mazzucchelli as the artist. Mazzucchelli and Miller had worked together in 1986 on the classic Daredevil story Born Again. One year later they reteamed to create Batman: Year One for DC. The Dark Knight Returns and Year One are arguably the two seminal titles that set the tone for most Modern Age Batman comics. And the creative talents behind both had previously collaborated on the Bronze Age Daredevil comics. Is it any wonder similarities emerged between the two?

FRANK MILLER & THEMATIC PARALLELS

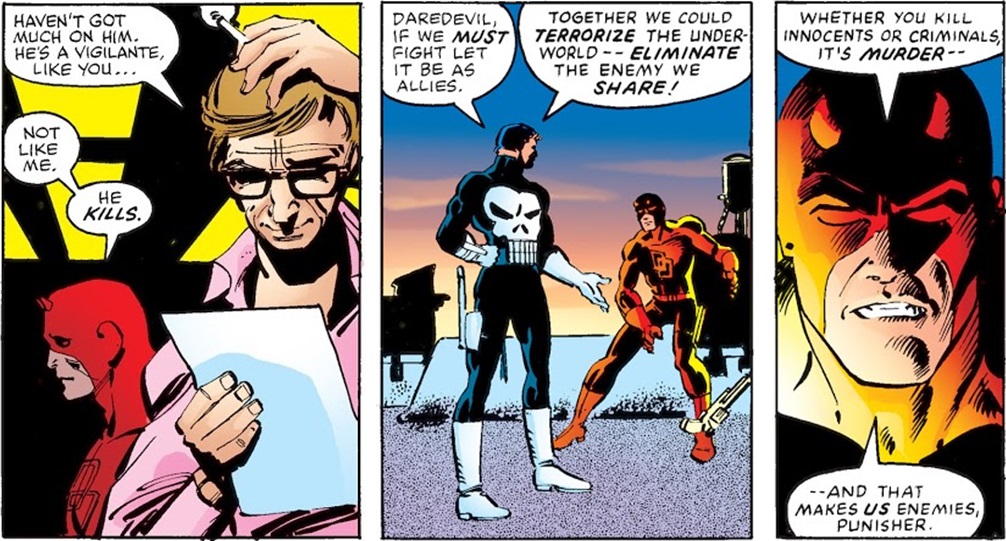

With the release of the first trailer for the second season of Marvel’s Daredevil on Netflix, many people commented on one particular line spoken by Jon Bernthal’s Punisher: “You know you’re one bad day away from being me?” Some accused Marvel of stealing this line from Alan Moore and Brian Bolland’s 1988 story Batman: The Killing Joke. A surprising number of Daredevil fans countered this by claiming the line originated in an earlier comic penned by Frank Miller. However no one seemed able to cite the precise issue in which Miller allegedly wrote the line. And the reason they were unable to do so is that it doesn’t exist. Miller never wrote that line for the Punisher. He did however write other pieces of dialogue in which comparisons were drawn between Matt Murdock and Frank Castle, with their contrasting attitudes to the sanctity of life being the one thing separating their otherwise similar crusades.

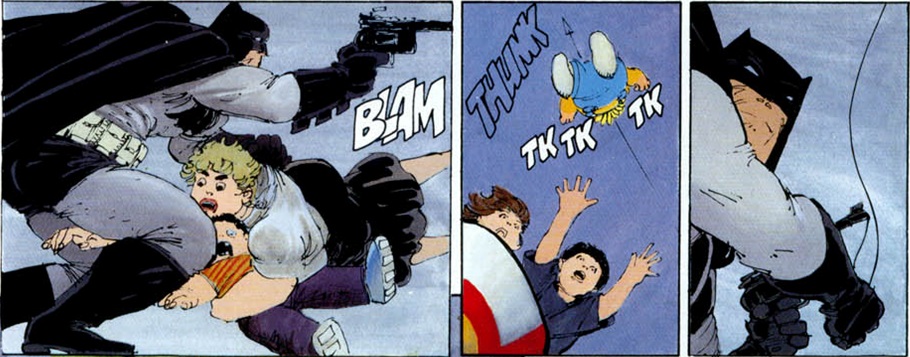

Panels from ‘Child’s Play’ (Daredevil Vol 1 #183, June 1982).

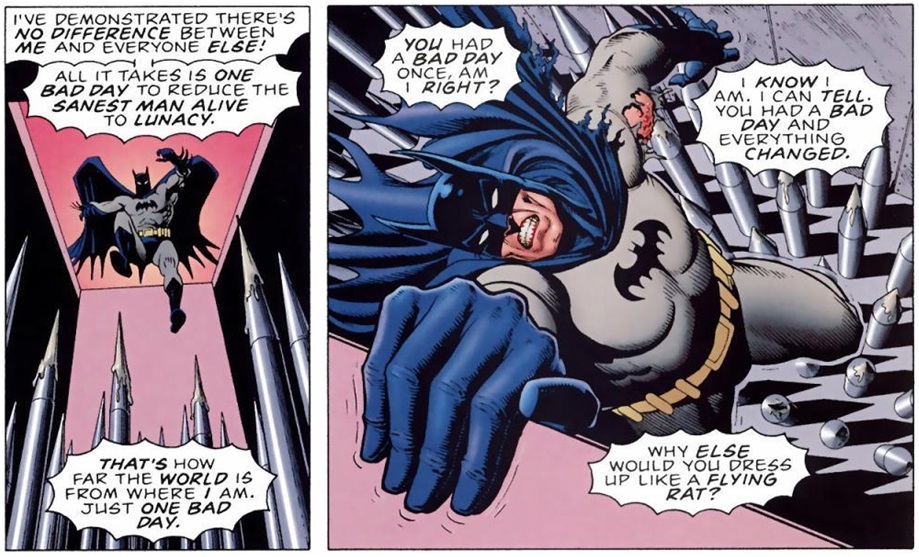

Moore explored similar diametric parallels between Batman and the Joker in The Killing Joke.

Panels from The Killing Joke (1988).

Does this mean the Daredevil TV show ripped off Moore, or that Moore ripped off Miller? No, of course not. The dynamic between hero and villain is something writers have been exploring since long before Batman and Daredevil even existed. Considering the similar tones of the comics, it’s only natural they’d end up addressing common themes and character dynamics.

Perhaps the most obvious example of thematic overlap is that of the hero’s ongoing resistance to taking life. Daredevil and Batman are both heroes who refuse to kill, yet they’ve both been tempted to break this rule under extreme circumstances. Perhaps the first Batman story to really delve into this struggle in any depth was A Death in the Family (1988-1989), where Bruce Wayne contemplated murdering the Joker after the latter killed Jason Todd. During this story arc, the burden of the Joker’s crimes was shown to weigh heavily upon Batman’s conscience.

Panels from ‘A Death in the Family: Part IV’ (Batman Vol 1 #429, January 1989).

Similar themes were explored a number of times during Miller’s Daredevil run where Matt contemplated killing Bullseye. His failure to do so burdened him with guilt over Bullseye’s subsequent victims, much the way Jason’s death haunted Bruce following A Death in the Family.

Panels from ’Gangwar!’ (Daredevil Vol 1 #172, July 1981).

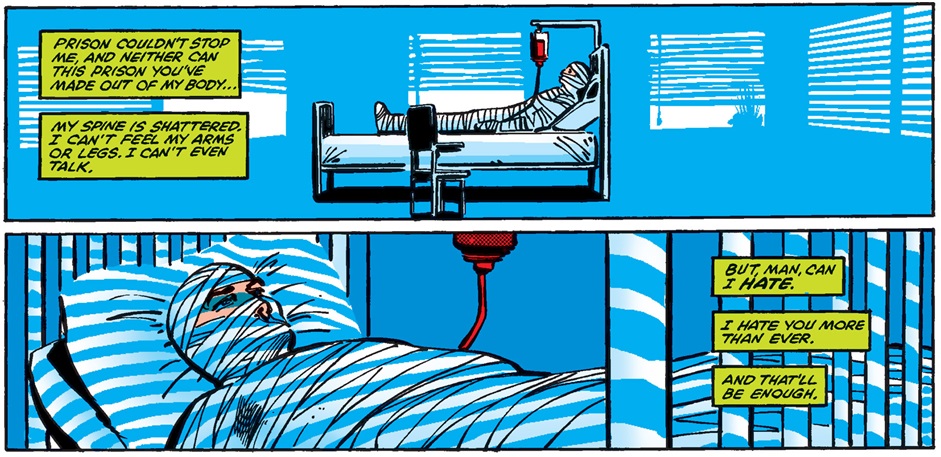

Matt Murdock would eventually take his vendetta against Bullseye to another level in ‘Last Hand’ (Daredevil Vol 1 #181, April 1982), dropping him from a great enough height to shatter his spine and leave him paralysed.

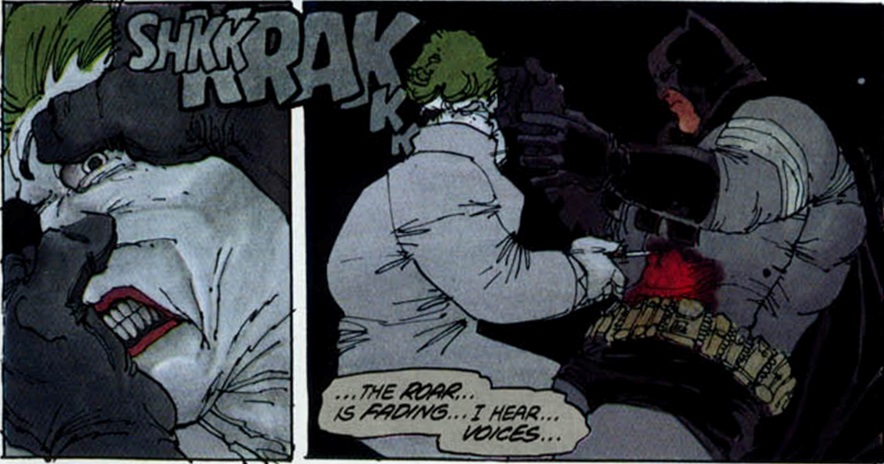

This issue was created by the team of Miller and Janson, who four years later would have Batman cross a similar line when he snapped the Joker’s neck in The Dark Knight Returns.

In both of these scenes, the villain was attacking the hero with a knife at the moment their spine was damaged. The slashing/stabbing blade symbolises the provocation engendered by the villain’s actions, constantly prodding at the hero’s moral constitution and testing their ethical resolve. This challenge to the hero’s abhorrence of killing is a recurring narrative in both the Daredevil and Batman comics and illustrates the lasting impact Frank Miller had on both characters.

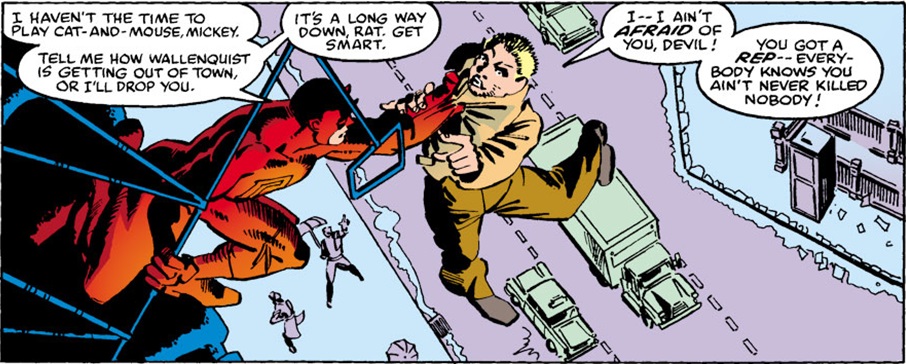

Miller’s take on Batman in The Dark Knight Returns was darker and more brutal than earlier depictions (with the notable exception of the early Bob Kane/Bill Finger stories from 1939-1940). One scene which has been replicated in countless subsequent comics is that of Batman dangling a criminal from a rooftop while he interrogates them. Similar scenes were already commonplace in the Daredevil comics by that point.

Panel from The Dark Knight Returns (1986) by Frank Miller and Klaus Janson.

Panel from ‘Elektra’ (Daredevil Vol 1 #168, January 1981), also by Frank Miller and Klaus Janson.

Note the similarities between the above Daredevil panel and the scene where Batman interrogates Sal Maroni in Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight (2008). In both scenes the criminal voices scepticism regarding the hero's willingness to drop them, only for the hero to do just that a moment later. While it’s extremely unlikely Nolan had even read this comic, let alone consciously referenced it, the similarity is still worth commenting on.

There is however another Batman movie which was consciously influenced by Miller’s Daredevil stories, and that’s Tim Burton’s Batman Returns (1992). In an interview with The Projection Booth Podcast (around the 3:10:50 time mark), Batman Returns screenwriter Daniel Waters admitted that Frank Miller’s Elektra: Assassin (1986-1987) miniseries had been a greater influence on his approach to the Catwoman character than the actual Batman comics had. It’s interesting he should say that, as the Michelle Pfeiffer incarnation of Catwoman also has notable similarities with the Daredevil villain Typhoid Mary: namely an origin story involving defenestration, death and rebirth, as well as her suffering from some form of identity disorder which leaves her struggling to curb her criminal urges while battling a hero she simultaneously loves and hates.

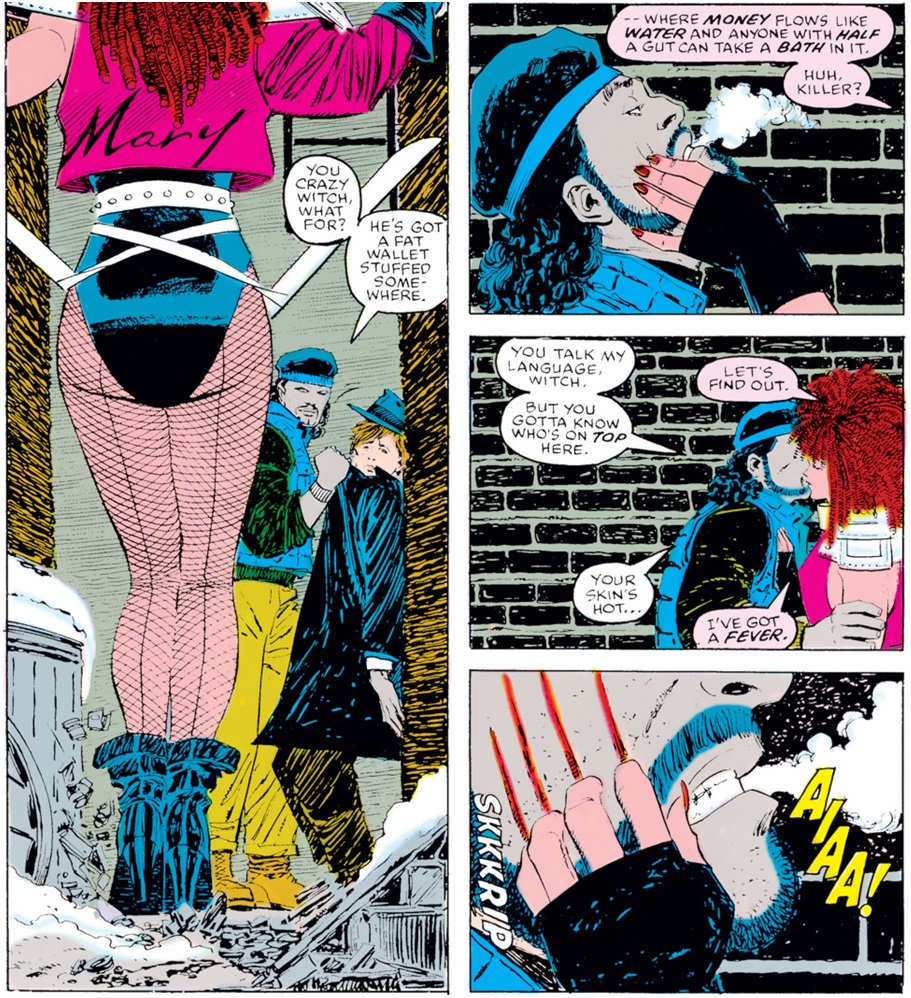

Above right: Typhoid Mary makes her costumed debut tackling a mugger in an alleyway in ‘Typhoid!’ (Daredevil Vol 1 #254, May 1988). Note how she scratches his face, similar to Catwoman's actions during the alleyway fight in Batman Returns.

I'd be remiss for not mentioning another Batman character on whom Miller left his indelible mark, and that’s Jim Gordon. Before Year One, Gordon had been depicted as an elderly police commissioner who mostly aided Batman from behind a desk. Miller re-envisaged the character as a younger police lieutenant who would actively fight alongside Batman on the front lines.

I'd be remiss for not mentioning another Batman character on whom Miller left his indelible mark, and that’s Jim Gordon. Before Year One, Gordon had been depicted as an elderly police commissioner who mostly aided Batman from behind a desk. Miller re-envisaged the character as a younger police lieutenant who would actively fight alongside Batman on the front lines.

Miller’s characterisation of Gordon in Year One follows his take on Ben Urich in the Daredevil comics. Both are portrayed as overworked, world-weary allies of costumed vigilantes, constantly butting heads with authority figures and struggling to stay clean of corruption while their families are threatened by their underworld adversaries. Year One and Born Again share similar scenes in which the hero, dressed in civilian attire, races to save a member of Urich's/Gordon's family from the mob. And once again, it was Miller’s take on these characters that defined how most later writers would depict them.

CAPED CRUSADER VS. OL’ HORN HEAD

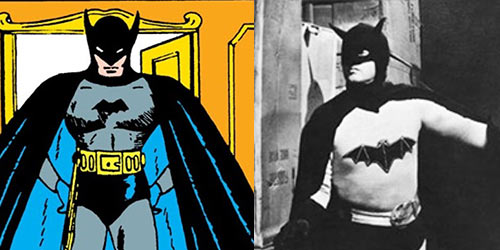

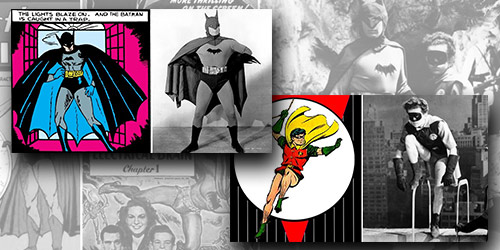

We’ve looked at the influence Frank Miller had on both Batman and Daredevil, as well as some of the common themes that emerged during the eighties. But how similar were these two heroes to begin with? They’re both expert martial artists and gymnasts, both in peak physical condition, both brilliant detectives with advanced knowledge of psychology, chemistry, engineering and interrogation techniques. But that description could apply to any number of superheroes. We're interested in the more specific parallels, such as the fact they both wear cowls featuring lenses and distinctive horn-like protuberances. In Batman’s case, the protuberances are meant to represent bat ears. While in Daredevil’s case they are meant to be devil horns. It’s no secret which hero donned the horned cowl first. Batman’s debuted in 1939, while Daredevil first wore his in 1964.

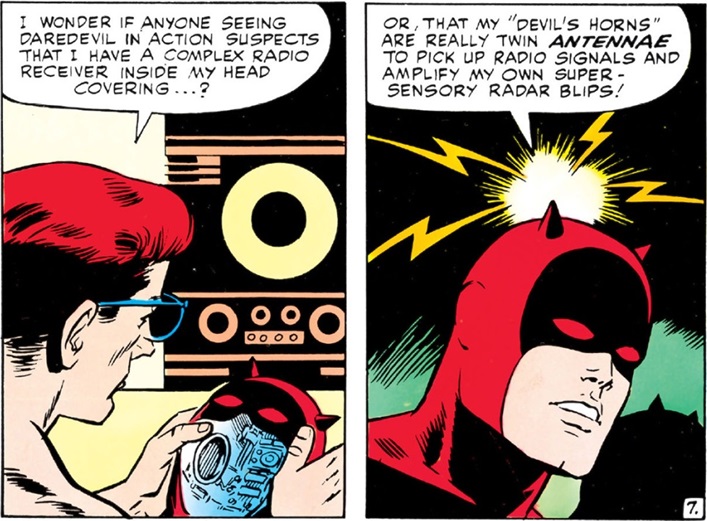

However Daredevil’s mask served a greater function than merely concealing Matt Murdock’s identity. His cowl was described as containing radio equipment as early as ‘The Stilt-Man Cometh!’ (Daredevil Vol 1 #8, June 1965), with his horns serving as antennae.

Batman’s cowl is described as containing similar technology in the modern comics, but this tech wasn’t introduced until a much later date.

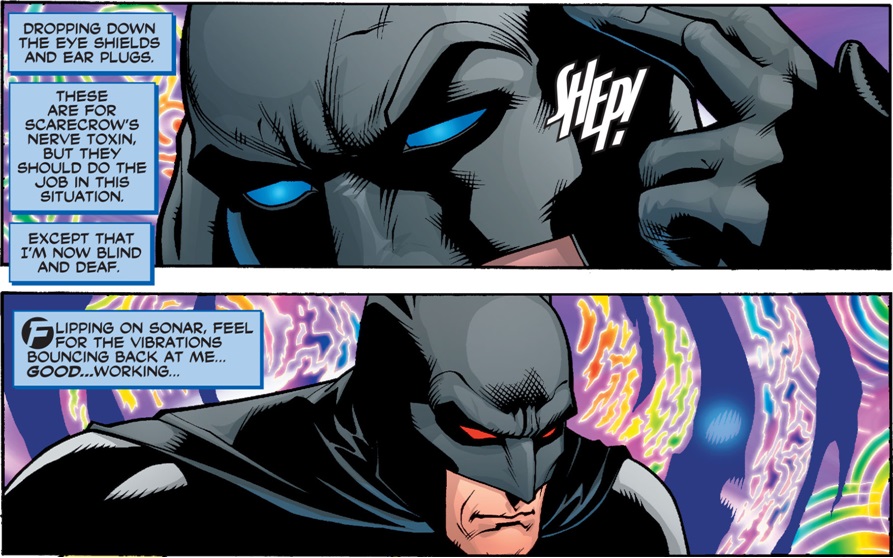

Details like this illustrate how the sixties Daredevil comics were forward-thinking in their rational approach to costume functionality; particularly in an era when Batman’s spontaneous production of bat-prefixed weaponry from his utility belt had become a pop culture joke. The Batman comics would take a little longer to address the functionality of Bruce Wayne’s arsenal, so I’d argue this was one area where Daredevil was definitely ahead of the curve. Meanwhile the Modern Age Batman has a cowl which features a built-in sonar system and lie detector. Another example of the Daredevil influence, or merely a coincidence?

Panels from ‘Franchise, Part II: The Away Team’ (Batman Vol 1 #647, January 2006). Note the lenses of Batman's mask turn red like Daredevil's when the sonar system is activated.

Panels from ‘The Court of Owls, Part III: The Thirteenth Hour’ (Batman Vol 2 #3, January 2012).

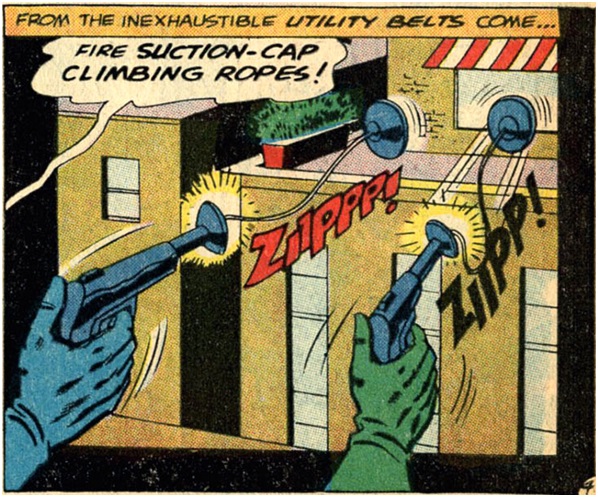

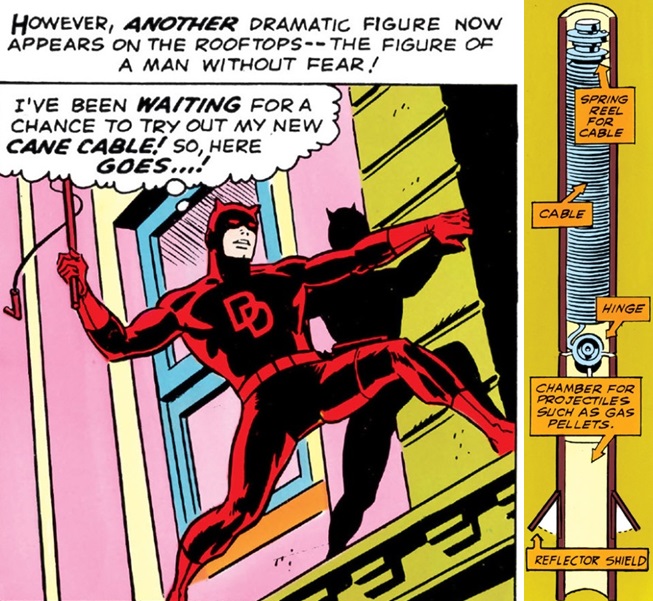

What about the rest of Batman’s arsenal? Bruce Wayne relies heavily on a wide and diverse range of weapons and gadgets, whereas Daredevil merely has his costume and billy clubs. The only real similarity in equipment, besides their protective suits, is that they both carry handheld grapple launching devices. Neither character can fly or move at super speed, so grapple launchers are essential for them to manoeuvre around the rooftops of their respective stomping grounds. But which character wielded a grapple launcher first?

Batman uses an early version of the spear gun/grapple launcher in The Dark Knight Returns, though this model lacked a retractable line.

Although the comic book Batman didn’t formally adopt the grapple gun into his standard arsenal until A Lonely Place of Dying (1989), his earliest use of a similar handheld device was way back in ‘A Touch of Poison Ivy!’ (Batman Vol 1 #183, August 1966). This pistol fired ropes with suction cups on the end instead of grappling hooks, but nevertheless conformed to the principle of a handheld projectile weapon that deploys cables for Batman to swing on. Although it lacked any kind of retraction mechanism, I’m still counting it as the earliest grapple gun.

Daredevil first launched a grapple line from his billy club back in ‘In Mortal Combat With... Sub-Mariner!’ (Daredevil Vol 1 #7, April 1965). The following issue, Daredevil Vol 1 #8 (June 1965), included a diagram which detailed the spring mechanism used to fire the cable.

The above cross-section of the cane is yet another example of how Marvel were taking pains to explain the functionality of Daredevil’s crime fighting methods at a time when Batman and Robin’s arsenal had become a deus ex machina best appreciated for its irony.

So as far as handheld grapple launchers go, Daredevil’s preceded Batman’s earliest model by over a year. Additionally, Daredevil’s billy clubs were described as containing a retractable cable mechanism, something which Batman’s grapple gun wouldn’t acquire until 1989. Before we move on from the subject of weaponry, it’s worth pointing out that Daredevil also wielded his dual billy clubs long before Nightwing adopted escrima sticks as his signature weapons.

VILLAINS & NARRATIVES

There’s some obvious overlap when it comes to Batman and Daredevil’s galleries of rogues. Take for instance the Daredevil villain Jester, who first appeared in ‘Nobody Laughs at the Jester!’ (Daredevil Vol 1 #42, July 1968). Here we have a criminal who dresses like a clown and wields lethal variations of traditionally harmless toys and pranks. Of course the Joker wasn’t the first villain based on the evil prankster concept, but he is unquestionably the most famous example of this archetype in the comic book medium. And although Jester has his own distinct origin story and MO involving media crimes, the comparisons between himself and the Joker remain inevitable.

The Joker debuted a full 28 years before the Jester.

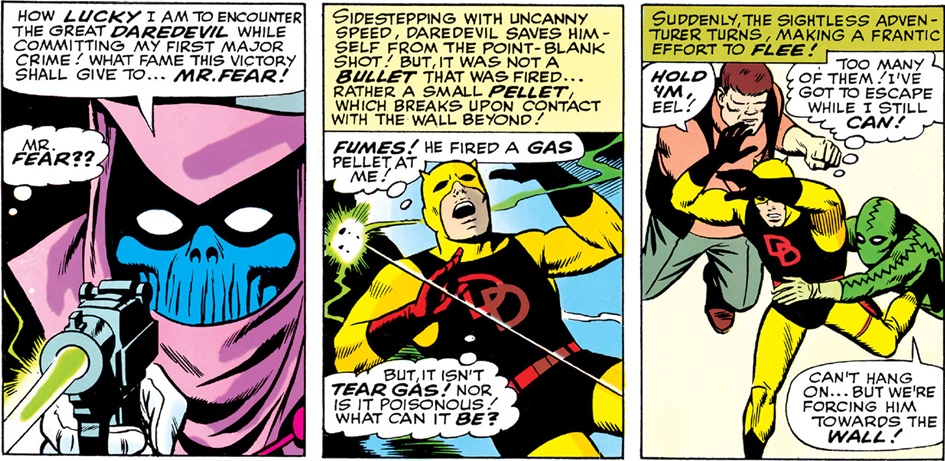

Then there’s the Daredevil villain Mister Fear, who made his debut in ‘Trapped... By the Fellowship of Fear!’ (Daredevil Vol 1 #6, February 1965). Mister Fear, as his name implies, is able to induce terror in his victims with the aid of his signature fear gas. This hallucinogen functions more or less identically to that used by the Batman villain Scarecrow, who first appeared in ‘The Riddle of the Human Scarecrow’ (World’s Finest Vol 1 #3, September 1941). As with the evil prankster motif, the idea of a villain who uses fear as their primary weapon did not originate in either of these comics. But the key element that suggests commonality between these two characters is their use of fear gas. And although Scarecrow predates Mister Fear by well over a decade, it was actually Mister Fear who used the fear gas first, as seen in the following panels from his debut story (February 1965).

During his two earliest appearances, Scarecrow relied on his costume and a simple gun to terrorise his prey. He didn’t deploy his own fear toxin for the first time until exactly two years after Mister Fear, in ‘Fright of the Scarecrow’ (Batman Vol 1 #189, February 1967).

Naturally the concept of fear toxin predates all of these stories. In fact Doctor Hugo Strange’s henchmen used a similar concoction back in ‘Professor’s Strange’s Fear Dust’ (Detective Comics Vol 1 #46, December 1940). But as far as the Scarecrow/Mister Fear comparisons are concerned, Mister Fear used the hallucinogen first.

While the Pre-Crisis Lex Luthor had been presented as an outlaw scientist, his Post-Crisis counterpart was portrayed as a corrupt businessman who masked his wickedness behind a public veneer of corporate legitimacy. Regardless of whether or not one character consciously influenced the other, it’s easy to see parallels between the Post-Crisis Luthor and the Bronze Age Wilson Fisk. And there are plenty of other analogues to be noted amongst Batman and Daredevil’s foes, from avian-themed criminals who imprison their captives in giant birdcages, to expert marksmen who never miss even the most improbable of trick shots.

Likewise there are many notable plotlines in the Batman and Daredevil comics that mirror each other. Take the classic Born Again story arc in which Matt Murdock’s nemesis discovers his true identity, preserves the secret and embarks on a campaign of psychological warfare to break Daredevil’s spirit. When Matt is at his lowest ebb his enemy strikes, destroying his home and physically breaking him. There then follows a period of convalescence where Matt is out of action and the world at large wonders what has become of Daredevil. When this failed to permanently defeat Daredevil, the architect of the scheme, Wilson Fisk, tried yet again to break Matt’s spirit. This time in Ann Nocenti and John Romita Jr’s ‘Typhoid Mary’ story arc (Daredevil Vol 1 #254-257 & #259-263, May 1988-February 1989). Fisk recruited Typhoid to capture Matt’s heart, break it, then force him to fight a gauntlet of classic foes before moving in for the kill when he’s reached the point of physical and emotional exhaustion.

In 1993 the Batman comics ran a storyline that was structurally very similar to both of these Daredevil arcs. That storyline was called Knightfall and featured a villain discovering Batman’s true identify, keeping this information secret, forcing him to fight a succession of classic rogues, then moving in for the kill and crippling him when he’s at breaking point. Meanwhile the storyline about Daredevil’s enemies sending a seductress (Typhoid Mary) as part of a larger scheme to break him was echoed in Grant Morrison’s Batman R.I.P. (2008), where Bruce’s love interest Jezebel Jet was revealed to be an agent of the Black Glove. Once again, it’s perfectly possible these parallels are mere coincidence. But they’re still worth noting.

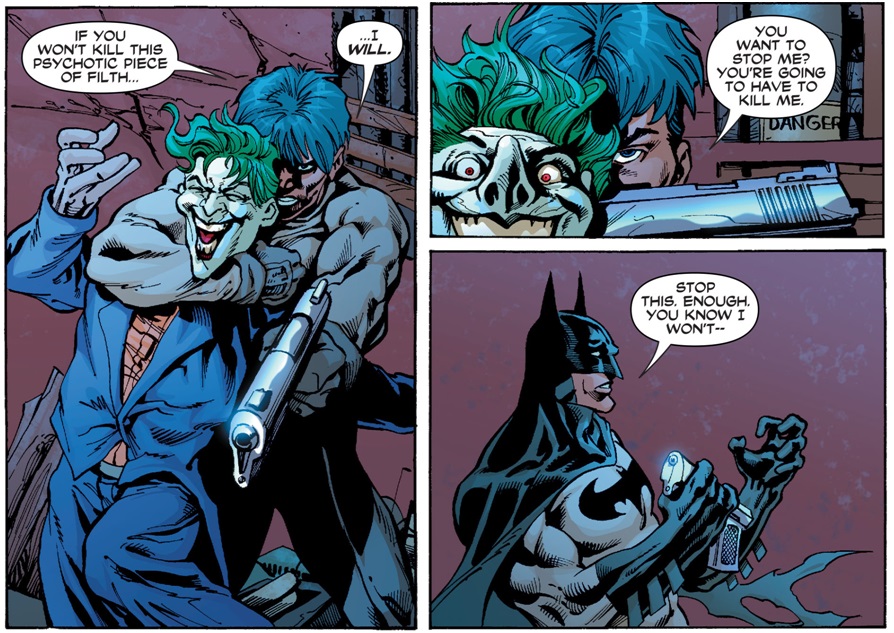

And how about the classic scene in Batman: Under the Hood (2005-2006) where Jason Todd hands Batman a gun and challenges him to use it or else he’ll execute the Joker.

Panels from ‘All They Do is Watch Us Kill, Part III: It Only Hurts When I Laugh’ (Batman Vol 1 #650, April 2006).

This scene was later adapted in the animated movie Batman: Under the Red Hood (2010). But doesn’t it bear a striking resemblance to an equally memorable scene from the Punisher/Daredevil crossover ‘The Devil by the Horns’ (Punisher Vol 4 #3, June 2000) in which Frank Castle chains up Daredevil with a gun taped to his hand and instructs him to use it or else he’ll kill a member of the Gnucci family?

Panels from ‘The Devil by the Horns’ (Punisher Vol 4 #3, June 2000).

And with this last comparison we find ourselves returning to the matter of shared themes, with Batman and Daredevil’s moral constitutions being tested by opponents who embody that which the heroes themselves could so easily become. And all it would take would be for "one bad day" to push them over the edge. Similar themes, similar stories, similar foes.

CONCLUSION

I could list countless more examples of themes, characters and storylines which crop up in both the Batman and Daredevil comics, but for now we’re merely scratching the surface. One point I’d like to emphasise is that just because parallels exist, it doesn’t mean that either comic is a rip-off of the other. Rather what we have here are two titles in the same genre evolving along parallel trajectories from the Silver Age onwards. Both comics derived influence from one another, but I would argue that Daredevil’s influence on Batman has proven more extensive than Batman’s influence on Daredevil. And this is largely due to the fact so many comic creators cut their teeth on the Daredevil comics, only to later work their same magic on Batman.

Gene Colan, Denny O’Neil, Frank Miller, Klaus Janson, David Muzzucchelli, Scott McDaniel, Ann Nocenti and Dan Chichester – just a few of the talented comic creators who worked on Daredevil before working on Batman. While others – such as Neal Adams, Marv Wolfman, Greg Rucka and Ed Brubaker – worked on the Batman comics first before later moving on to Daredevil. It’s hardly ‘ripping off’ if the same people crafted both titles. And since the majority of comic creators operate on a freelance work-for-hire basis anyway, it makes sense that they'd apply their skills to similar characters for both DC and Marvel.

As I stated earlier, there are just as many differences between Bruce Wayne and Matt Murdock as there are similarities. One is a wealthy capitalist in charge of a multibillion-dollar corporation, with a vast array of hi-tech weapons and vehicles at his disposal. The other is a blind Irish-American lawyer operating his own legal practice during the day, while prowling the rooftops of New York at night dispensing an altogether more brutal form of justice. Batman and Daredevil are kindred crime fighters, both alike and dissimilar in a myriad of ways. And they’ve both enjoyed the input of some of the most talented creators working in the comic industry today.

If we insist on viewing these comparisons through the lens of a simple DC versus Marvel paradigm, then the outcome yields only one true winner – and that’s us, the fans who get to enjoy both characters in equal measure.

May their adventures continue for many more years to come.

comments powered by Disqus

by The Dark Knight

by The Joker

by The Joker

by The Dark Knight

by The Joker

by The Dark Knight

by Slash Man

by The Joker

by The Joker

by The Laughing Fish